Hi, I’m Lexi, a multidisciplinary graphic designer in NYC, exploring print + digital design with curiosity, storytelling,

and creative ideas.

A is for Access

How do we as designers control the narrative and visual meaning of accessibility?

With 1.3 billion people having a significant disability, how we create access and who we include in the process is essential to providing adequate support.

As designers, the Americans with Disabilities Act, and other similar international legislation, outline baseline standards for inclusion. I believe collective commitment for collaborative, accessible design is needed to improve our quality of life and well-being, and ensures that a future includes us.

︎︎︎ Course: CD Thesis

︎︎︎ Role: Writing & Research, Editorial Design

︎︎︎ Deliverables: Spiral-Bound Book, Mini Design Manifesto

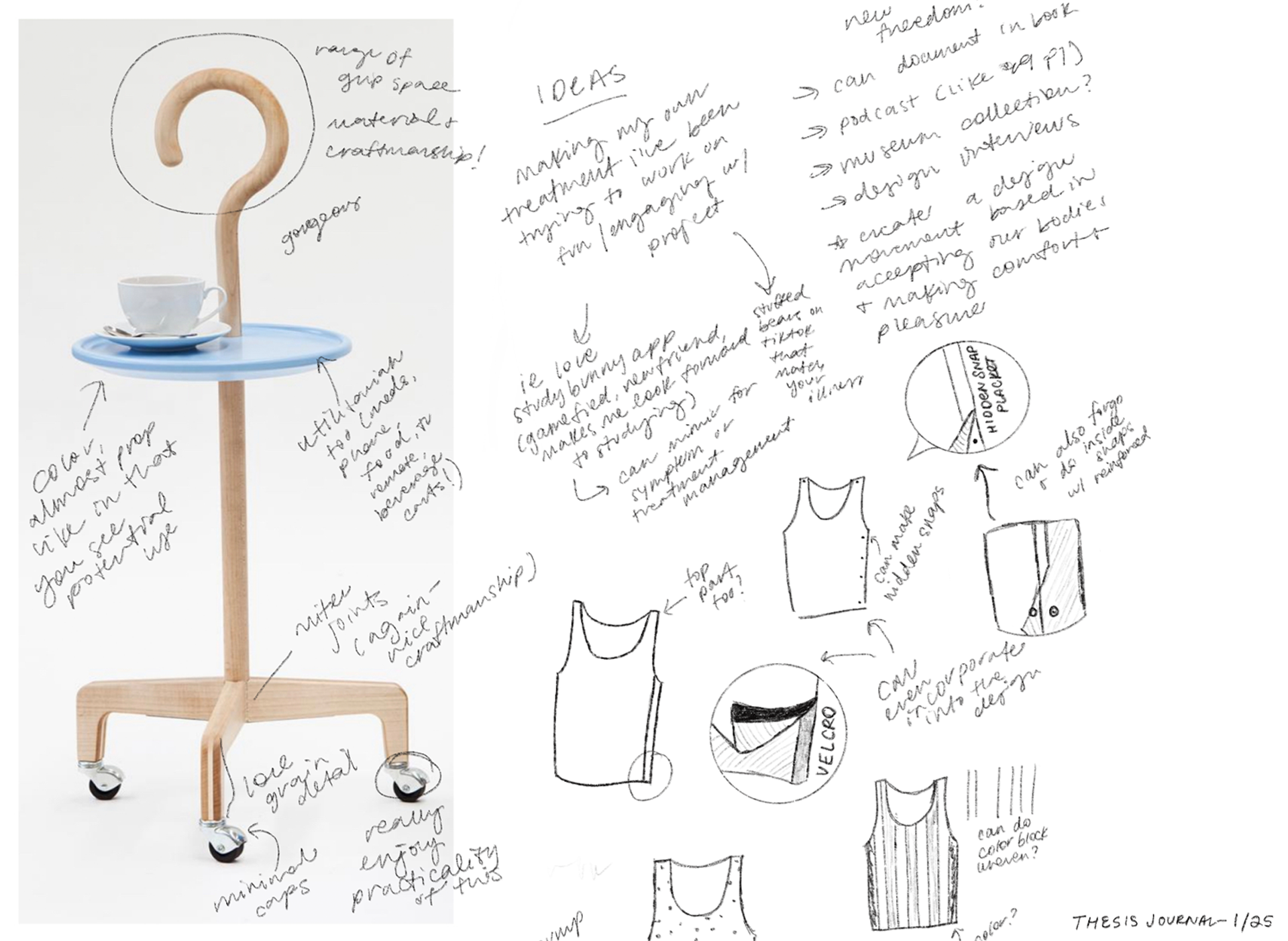

It all began to click when I saw this cane...

The beauty and presence of Studio Lanzavecchia + Wai’s cane stopped me in my tracks. As a designer passionate about accessibility, and with my own chronic health conditions, the details in the design of this mobility aid was immediately apparent. The smooth finish, the wood detailing joints, clean finish of the plate, and extended curved handle, were some of the specs I kept thinking about.

I don’t even need this mobility aid, but seeing its functional and stylistical blend, as well as an outlet for personal style questioned what accessible design thinking (and outcomes) could look like.

I’m also reminded of my grandma, who used various mobility aids in her late life. She was notoriously stubborn and did many things independently for as long as she could, saying that she didn’t want to “feel old.”

Similar comments were made about the bland and sterile design of her mobility aids, feeling out of place in her home. Seeing how beautifully this cane adapts to personal style and environments, I always wondered what her experience using it would be.

Ac·cess

“The power, opportunity, permission, or right to come near or into contact with someone or something.More specifically, it refers to efforts to reform architecture and technology addressing diverse human abilities.”

––Bess Williamson

Throughout Professor David Gissen’s class, it was imperative we study disability studies history alongside design development, as key historical figures helped shift laws and understanding of what is accessible design and why we needed it.

When understanding design for disability, its imperative we know the history, like the 504C sit ins, capitol crawl, as well as important historical figures that paved the way for the legislation we have, which now is impacting how we design. These included Brad Lomax (second picture) who was also a member of the Black Panther Party, connecting important resources to support the nearly two week sit in at the capitol. To his left is Judith Hueman, a life-long advocate for disability legislation.

These two figures, their different lived experiences with intersectional identities, and work are some of the examples and perspectives I knew I needed to include in sampled writing from others, as well as my own research.

The varying treatment of government programs, private practices, and ranging privillege amongst people with disabilities in America is crucial in understanding the standards we create accessible design for, who has access to it, included in research opportunities, and is even making it.

How do we analyze how ‘accessible’ design is, and how the media portrays it to be?

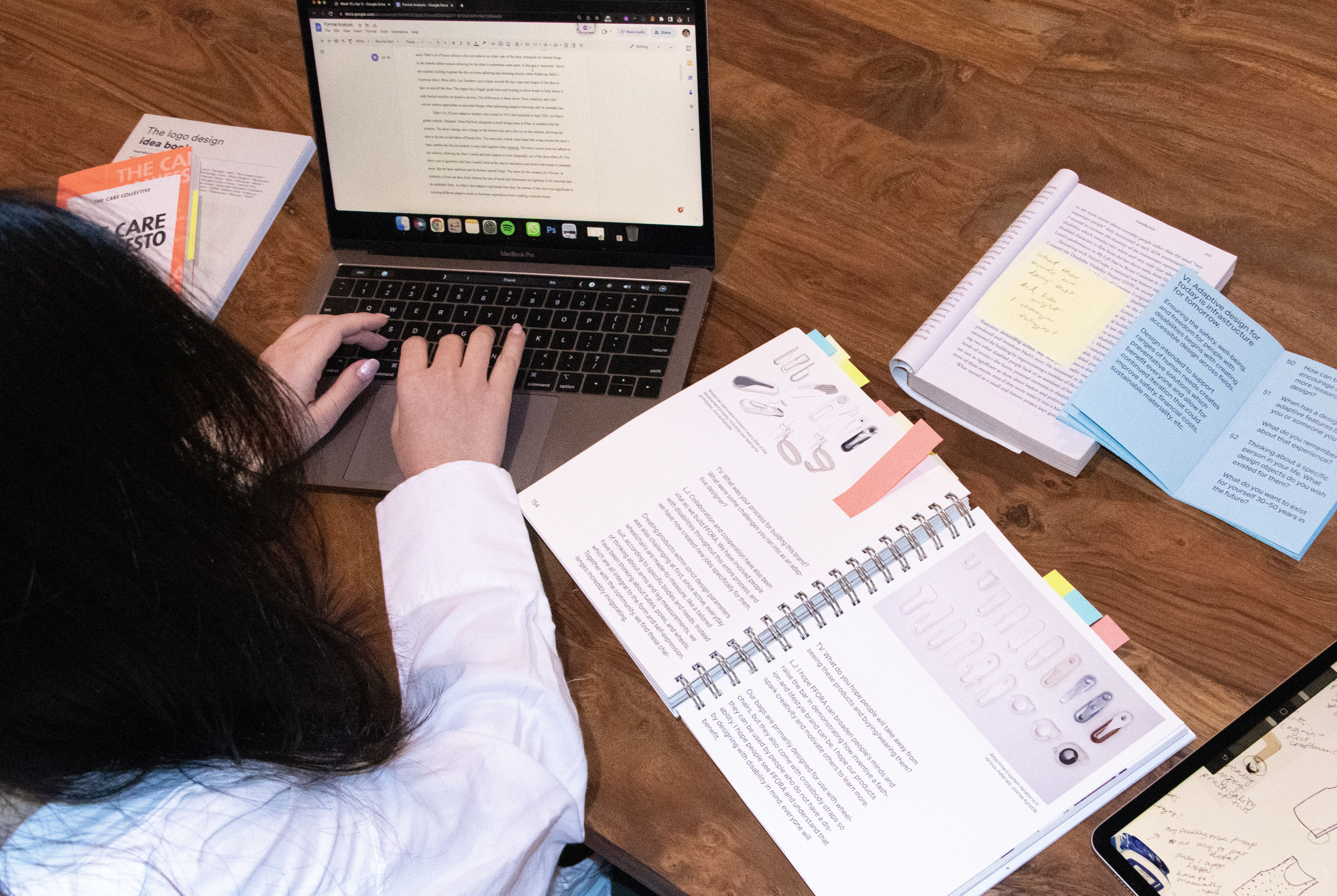

Throughout my time at Parsons, I analyzed multiple projects and wrote papers that discuss what accessibility design can look like and how disability is addressed.

My most detailed paper titled, “Evolving Models” analyzed Nike’s GO FlyEase Sneaker production process and critiqued opportunities for more inclusive, disability-centered user testing, as well equitable product development and distribution.

Research looked at the history of accessible design in America (Bess Williamson), the beginning of prosthetic design, design frameworks like the DARE model, and explicit differences between ‘accessible’ and ‘universal’ design to understand the work we make.

I also attended Professor David Gissen’s course, “The Design of Disability,” which connected my own mini research assignments and projects into the book Amid Access, including smaller pieces on the NYC Subway access and access in the US prison system.

Lastly, media produced by people with disabilities, including Alice Wong’s

Disability Visibility Project podcast, The Politics of Disability by Mary Fashik, design talks from Liz Jackson, and multimedia from Imani Barbarin (@crutches_and_spice) were some personal perspectives I consumed to understand multiple perspectives of access.

A is for Access

Focusing on accessible design beyond its function, A is for Access highlights work emphasizing delight, personal expression, and innovation for people with disabilities.

The project is composed of three complementary projects: a digital archive, a book, and a manifesto.

Tools for making for the creative process

Though this project was intended for designers, the call for accessibility speaks louder and farther than the industry alone. It is my intention that readers alike can apply these concepts to their own practice, and bring that personal responsibility to their work.

Desired Impact:

I. Deeper understanding of the limitations that government requirements for access has.

II. Widen awareness of implicit biases design has for favoring the abled-bodied user.

III. Shift to design “with,” rather than “for.”

IV. Determination to create change.

Introducing the book––

Amid Access

”Amid Access” provides a more in-depth exploration of accessible design thinking with history, disability studies, and design case studies. The book serves as a beginner blueprint to understand what access is and where we need it. It’s design applies text formatting and materiality standards to increase legibility.

Introduction––What is Disability?

Various models of disability with a brief historical overview of rights for people with disabilities in the US, written by Sunaura Taylor.

I. The History of Medicalized Design

Understanding the historical impact of tuberculosis, sanatoriums, and hospital design, and historical encounters with those spaces.

II. Mainstream Design for Accessibility

Wide-scale, corporate approaches to accessible and universal design written by Lexi O’Neill.

III. Designing with Personal Perspective

Selected work from designers with disabilities who show importance of personal experiences in their work and design field.

IV. Collaborative Design for Access

Historical and modern examples of collaborative making spaces that center impactuful adaptive design.

V. Where Access Needs Exploring

Discussion of modern day accessibility improvements that are needed, including NYC metro, prisons, and commercial airlines.

VI. Universal Design & Approaching Access

Reflective writing of Aimi Hamraie, who asks with a wide-variety of approaches to design, is universal design enough?

Included Texts in Amid Acces*

Sunaura Taylor, Ellis Woodman, Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wilson, Liz Jackson, Michael Gold, Alex Haagaard, Rua Williams, Leila McNeill, Meg Miller, Yuchen Zhang, Sara Radin, Correctional Service of Canada, Michael Gold, Aimi Hamraie

*Please note: this is a school project. Included texts were not published or distributed.

After compiling Amid Access, I wanted to know what my studio practice will look like.

How will I apply the accessibility research I’ve found?

Learnings from the archive and design research transformed into the design manifesto, entitled “Designing Accessible Futures.”

This short, pocket-size text guides designers through questions about what we are making, how we might integrate accessibility, and understanding our own biases.

The text contains 90 reflective questions under 10 key points. They range from specifics on current work to larger, long-term questions on what advocacy and inclusion in our life can look like.

The passion sparked in this project has made it an evolving work beyond my thesis.

In creating this project, I knew that there was so much more I wanted to create, write about, and learn about. Right now, I am continuing to collect and read about adaptive and inclusive design research and making, working to synthesize them into a living archive.

I’ve also delved more into texts and personal experiences with disability, adaptive textile prototyping, and exploring learning spaces.

Some recent discoveries including the Andrew Heiskell Talking Book Library, large print format guidelines from the American Publishing House for the Blind, and personal explorations into surface design for port-acccessible clothing for treatments (like chemotherapy).